Not all green water is equal. The species at the base of your food web determine whether nutrients become trophy fish — or surface scum. Understanding this distinction changes everything about how you manage a pond.

Every pond is a food web — a chain of energy transfer from the smallest organisms to the largest predators. Understanding this chain is the key to understanding why some ponds grow trophy fish and others don't, even when both appear equally "green."

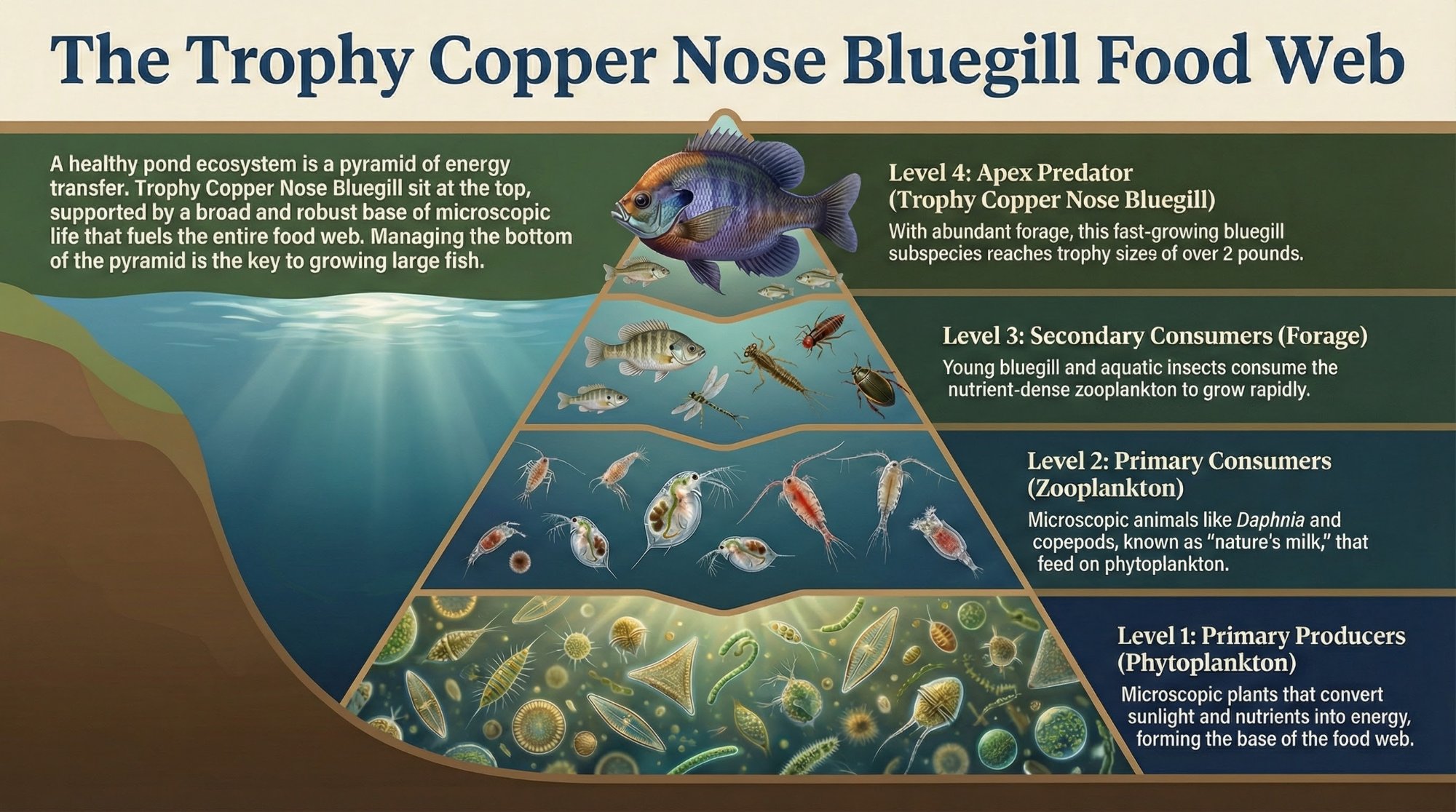

The food web in a productive pond follows a trophic pyramid with four essential levels:

Primary Producers (Phytoplankton): Microscopic algae — diatoms, green algae, and cyanobacteria — form the base of the pyramid. They convert sunlight and dissolved nutrients into living biomass. Everything above them depends on the quality and quantity of what they produce.

Primary Consumers (Zooplankton): Organisms like Daphnia (water fleas) and copepods graze on phytoplankton, converting plant energy into animal protein. They are the critical link — the mechanism that turns algae into food that fish can actually eat.

Secondary Consumers (Forage Fish): Larval and juvenile fish, including bluegill fry and young-of-year Coppernose, feed heavily on zooplankton during their first weeks of life. This is when growth rates and survival are determined.

Apex Predators (Trophy Fish): Adult bass, mature Coppernose bluegill, and other sport fish sit at the top. Their size, condition, and reproductive success are a direct reflection of the energy flowing up through every level below them.

For decades, pond management has operated on a simple assumption: more nutrients make more algae, more algae make more fish. Success was measured by Secchi disk visibility — target 18 to 24 inches of green water and you're doing it right.

This approach gets one thing correct: phosphorus drives biomass. But it makes a critical error by treating all algal biomass as equally valuable. It isn't.

Heavy phosphorus loading — especially without attention to nitrogen ratios — frequently drives the phytoplankton community toward cyanobacteria (blue-green algae). Cyanobacteria are fundamentally different from diatoms and green algae in ways that matter enormously for the food web:

Cyanobacteria form large colonies surrounded by mucilaginous sheaths that zooplankton physically cannot handle. Many species produce toxins (cyanotoxins) that harm grazers. And nutritionally, they are profoundly deficient — lacking the essential fatty acids that zooplankton need to reproduce and grow.

Because zooplankton cannot effectively graze cyanobacteria, the energy contained in those blooms does not move up the food chain. Instead, it accumulates as surface scum, dies, and decomposes — consuming dissolved oxygen rather than producing fish flesh. This is the trophic dead end: a pond full of green biomass that produces nothing but water quality problems.

The traditional approach of measuring success by water color has it exactly backwards. A pond with less total biomass but dominated by the right algae — diatoms and green algae — will outproduce a hypereutrophic pond choked with cyanobacteria every time, because the energy actually reaches the fish.

If cyanobacteria domination is the problem, what determines which algae win? The answer lies in stoichiometric steering — the deliberate management of nutrient ratios to favor desirable phytoplankton species over undesirable ones.

Instead of simply "loading" more nutrients into a pond, effective management requires "steering" the ratios of Nitrogen (N) and Phosphorus (P) to control which algae dominate.

The mass ratio of Nitrogen to Phosphorus (N:P) is the single most important chemical lever for determining phytoplankton community composition. Here's why:

Cyanobacteria have a unique competitive advantage — they can fix atmospheric nitrogen. This means they thrive in environments where dissolved nitrogen is scarce relative to phosphorus. When the N:P ratio drops below 20:1, nitrogen becomes limiting, and cyanobacteria outcompete diatoms and green algae because they don't need water-column nitrogen to grow.

Maintaining N:P above 20:1 removes that advantage. When dissolved inorganic nitrogen is abundant, diatoms and green algae — which are faster growers when nitrogen is available — outcompete the cyanobacteria. The bloom shifts from inedible scum to grazeable food.

Phosphorus controls the total amount of algal biomass. Traditional management pushes phosphorus high to maximize "greenness." But the optimal approach targets a moderate range — enough phosphorus to sustain a productive bloom, but not so much that the system becomes hypereutrophic and impossible to steer. Think of phosphorus as the throttle on an engine: more isn't always better. There's a range where the engine runs efficiently.

If phosphorus is the throttle, nitrogen is the steering wheel. Nitrogen availability determines which algae dominate. By maintaining high dissolved inorganic nitrogen relative to phosphorus, you direct the community toward diatoms and green algae — the edible, nutritionally rich species that fuel the food web.

Critical note: Stoichiometric steering is precision work, not a guessing game. It requires water testing to know where your pond's nutrient ratios currently stand before any adjustments are considered. Every pond is different, and the starting point determines the intervention.

The distinction between diatoms/green algae and cyanobacteria isn't just about whether zooplankton can physically eat them. The nutritional difference is profound and directly impacts every level of the food web above.

Diatoms are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), specifically Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) — the same omega-3 fatty acids valued in human nutrition. These compounds are essential for zooplankton reproduction, growth, and survival. Zooplankton cannot synthesize these fatty acids on their own; they must obtain them from their diet.

Cyanobacteria are deficient in these essential sterols and fatty acids. A zooplankton population feeding on cyanobacteria is the aquatic equivalent of an animal on a starvation diet — technically eating, but not receiving the nutrition needed to reproduce or grow.

| Characteristic | Diatoms & Green Algae | Cyanobacteria |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Size | Small, unicellular — easily grazed | Large colonies, mucilaginous sheaths |

| EPA/DHA Content | High — essential for zooplankton | Deficient or absent |

| Toxicity | Non-toxic | Many species produce cyanotoxins |

| Zooplankton Grazing | Efficiently grazed by Daphnia & copepods | Resists grazing — clogs feeding apparatus |

| Energy Transfer | Efficient — energy reaches fish | Trophic dead end — energy trapped |

| DO Stability | Moderate biomass, stable oxygen | Extreme blooms, wild DO swings |

When the food chain is streamlined — diatoms → zooplankton → forage fish → predator — energy transfer is highly efficient at each step. Less is lost to waste and respiration because each organism is optimally suited to consume what's below it. This is why a pond with moderate, high-quality biomass outperforms a pond with massive, low-quality biomass. The streamlined chain produces more fish per unit of nutrient input.

If diatoms and green algae are the right fuel, then zooplankton — specifically Daphnia (cladocerans) and copepods — are the engine that converts that fuel into fish. Without an active, abundant zooplankton community, even a perfectly composed phytoplankton bloom cannot feed a fishery.

Daphnia are large-bodied cladocerans that filter-feed on phytoplankton suspended in the water column. A healthy Daphnia population can filter the equivalent of the entire pond volume in a matter of days, dramatically improving water clarity. Their large body size makes them an exceptionally energy-dense food source for juvenile and forage fish.

Copepods are selective grazers — they actively choose high-quality food particles. In a pond dominated by diatoms and green algae, copepods thrive. In a cyanobacteria-dominated system, they struggle or disappear entirely. Copepod nauplii (larval stages) are also a critical first food for newly hatched fish fry, making copepod reproduction essential for year-class survival.

Zooplankton community composition is one of the most powerful diagnostic tools in pond management. A sample dominated by large-bodied Daphnia and copepods tells you the food web is functioning. A sample showing only small rotifers and protozoa — or nothing at all — signals a broken food web, regardless of how green the water appears.

This is why zooplankton assessment is as important as water chemistry testing. The chemistry tells you what the pond should be able to support; the zooplankton tell you what it actually is supporting.

The composition of the food web doesn't just affect fish growth — it directly determines dissolved oxygen stability, which is the difference between a thriving pond and a fish kill.

When cyanobacteria dominate and zooplankton cannot graze the bloom, algal biomass accumulates unchecked. Dense surface blooms create extreme dissolved oxygen conditions: supersaturation during the day from photosynthesis, and dangerous depletion at night when the massive biomass respires. This "boom and bust" oxygen cycle is the direct cause of overnight fish kills in eutrophic ponds.

Dense surface blooms also shade the water column, preventing photosynthesis at depth. The result is a "top-heavy" oxygen profile where the surface is supersaturated but the bottom is anoxic — creating exactly the stratification conditions that lead to turnover-related fish kills.

When the food web is functioning — diatoms being actively grazed by copepods and Daphnia — total algal biomass stays within an optimal range. Zooplankton continuously consume phytoplankton, preventing the unchecked accumulation that causes extreme DO swings. The result is a moderated, stable bloom that produces oxygen during the day without crashing it at night.

This is the fundamental difference between optimization and maximization. An optimized food web produces moderate, stable biomass that efficiently transfers energy to fish while maintaining safe dissolved oxygen. A maximized system produces enormous biomass that goes nowhere, consuming oxygen and destabilizing the entire system.

The Slab Lab — a 3-acre trophy Coppernose bluegill pond in Alabama — provides a dramatic, real-world case study of food web collapse and deliberate rebuild. Documented across a YouTube video series by Natural Waterscapes, the transformation shows what happens when you shift a pond's biology from the base of the food web up.

Before the Reset: The Slab Lab suffered a catastrophic fish kill in the summer of 2024. The phytoplankton community was dominated by cyanobacteria — over 535,000 cyanobacteria cells per milliliter. The food web was broken at the base. Despite abundant green biomass, energy was trapped in inedible species. Zooplankton assessments showed the community was dominated by protozoa — the lowest-quality grazers — with no significant copepod or Daphnia populations.

The Intervention: The reset combined multiple approaches: MetaFloc to bind legacy phosphorus in the sediment, Kasco surface aerators to stabilize dissolved oxygen, and deliberate nutrient ratio management to shift the phytoplankton community away from cyanobacteria and toward diatoms and green algae.

The Result: Cyanobacteria cell counts dropped from over 535,000 cells per milliliter to zero. Total phytoplankton fell to just 4,500 cells per milliliter. The remaining phytoplankton was entirely composed of diatoms and green algae. The food web base had been completely rebuilt.

The December 2025 zooplankton assessment — conducted by Natural Lake Biosciences — confirmed that the food web was responding. The results were striking for a winter baseline sample:

Copepods dominated the community, representing 85% of both abundance and biomass. Cyclopoid copepods were the primary group at 28.8 individuals per liter — a robust winter population indicating an established, reproducing community. Active nauplii (copepod larvae) confirmed that reproduction was occurring even during the cold season.

Daphnia were establishing. While ranked fourth in abundance, Daphnia ranked second in total biomass at 16.3 µg/L — reflecting their large body size and signaling a population poised for rapid spring expansion as water temperatures rise and phytoplankton production increases.

Zero protozoa were detected. In the pre-reset assessments, protozoa — the smallest, least nutritionally valuable grazers — had dominated the zooplankton community. Their complete absence in the December sample, replaced by copepods and Daphnia, represents a fundamental shift in food web quality.

This December baseline establishes the foundation. As the Slab Lab moves into spring and summer 2026, these zooplankton populations are positioned to expand rapidly — supported by the diatom- and green-algae-dominated phytoplankton community that is now in place. The food web that will feed the next generation of trophy Coppernose bluegill is being built from the bottom up.

SLABLAB at shop.naturalwaterscapes.com for $20 off orders over $100.

Managing a pond food web starts with understanding what's happening in your water. These tools and treatments address the key factors discussed on this page — from diagnostics to nutrient control to biological support.

SLABLAB at shop.naturalwaterscapes.com for $20 off orders over $100.

Green water indicates phytoplankton biomass, but the species composition determines whether that biomass is productive or harmful. Cyanobacteria-dominated green water is a trophic dead end — the energy is trapped in organisms that zooplankton cannot graze. Green water dominated by diatoms and small green algae is highly productive because zooplankton efficiently convert it into food for fish. The color alone tells you nothing about food web quality.

The Nitrogen-to-Phosphorus ratio (N:P) by mass determines which algae dominate. Below 20:1, nitrogen becomes limiting, giving cyanobacteria a competitive advantage because they can fix atmospheric nitrogen. Above 20:1, dissolved nitrogen remains available, favoring diatoms and green algae that rely on water-column nitrogen. Maintaining N:P above 20:1 is the primary chemical lever for suppressing cyanobacteria and building a productive food web.

Diatoms are single-celled algae with silica cell walls. They are rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) — specifically EPA and DHA — the same omega-3s valued in human nutrition. These are essential for zooplankton reproduction and growth. Cyanobacteria lack these fatty acids, form colonies too large for zooplankton to handle, and often produce toxins. A diatom-dominated bloom efficiently feeds the food web; a cyanobacteria-dominated bloom traps energy at the base.

A trophic dead end occurs when energy is trapped in an inedible form at the base of the food web. In ponds, this happens when cyanobacteria dominate — zooplankton cannot graze them, so the energy never reaches fish. The biomass accumulates as surface scum, decomposes, and consumes oxygen. A pond can appear highly productive (lots of green biomass) while actually being a biological dead end that produces nothing but water quality problems.

Copepods and Daphnia are the critical link between phytoplankton and fish. Daphnia are large-bodied filter feeders that can clear the water column while converting algae into energy-dense food. Copepods are selective grazers that target high-quality food particles. Together, they turn microscopic plant life into animal protein that fish can consume. Their larvae (nauplii) are also a critical first food for newly hatched fish fry — making zooplankton reproduction essential for year-class survival.

Cyanobacteria blooms create extreme dissolved oxygen swings — supersaturation during the day, dangerous depletion at night. When zooplankton actively graze the phytoplankton, they prevent this biomass accumulation, keeping DO within a moderate, stable range. A functioning food web is itself a dissolved oxygen stabilizer: the grazing pressure prevents the unchecked bloom growth that causes overnight crashes and fish kills.

Every improvement starts with diagnostics — water testing and biological assessment. Key interventions include nutrient ratio management, phosphorus binding for legacy-loaded sediments, aeration for dissolved oxygen stability, and biological support through proper fish stocking. Some ponds may benefit from precision fertilization in nutrient-deficient waters, but this is not a blanket recommendation — it requires water chemistry data to determine whether and how to fertilize. Contact a pond management professional for guidance specific to your pond.

The food web is one piece of the puzzle. Explore how phosphorus, aeration, and emergency response connect to build a complete understanding of pond management.

Watch the full Slab Lab video series on YouTube — from fish kill to food web rebuild, every step documented.